Law, Philosophy, and Political Science

What should the law be? Majority rule sounds dandy enough until the other side wins. Both liberals and conservative resort to the Constitution when it suits them. But where does our Constitution – or any constitution derive moral authority? Tradition? Religion? Philosophy?

And once you have determined what the laws should be, how do you make the government actually enforce those laws without doing naughty things on the side? It’s harder than oft advertised.

Below are some works on these subjects worth reading. They vary in quality. Some are worth incorporating into your thought. Some are interesting but deeply flawed. A few I provide as object lessons of bad reasoning that caught on anyway.

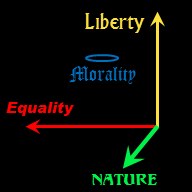

Axiomatic Law

Suppose you had no legislature at all, and no shared tradition to fall back on. On what basis could private protection agencies and civilian militias resolve disputes?

Murray Rothbard suggests Self Ownership as an overriding principle in The Ethics of Liberty, and attempts to derive a complete legal code from this one principle – and its corollary, the Zero Aggression Principle. I found this work compelling back when I was a college freshman. I was leaning in the anarchist direction, and Rothbard wrote well and with great passion.

But Dr. Rothbard was an economist, not a legal scholar, and his hatred of government got in the way of the scholarly process. He resorted to dismissive hand-waving when inconvenient truths got in the way of his elegant logical edifice.

Read this one as a warm-up, but beware of falling into Rothbard’s meme trap. To focus solely on the Zero Aggression Principle is to overlook other important moral considerations!

Richard Epstein is a real legal scholar, and quite respected in some circles. In Simple Rules for a Complex World, he takes on the challenge of axiomatic law while addressing those tricky edge conditions that Rothbard dismissed, but legal scholars find interesting. He clearly demonstrates where Rothbard’s axiom is incomplete, and adds four more to make a complete legal edifice. (Whether this legal edifice is optimal is an exercise I leave to the reader.)

This is a much better work than The Ethics of Liberty, but it is a harder read. I need to reread it myself when time permits.

Against Natural Law

Natural Law arguments add a delightful authority and logical consistency for those who appreciate the consequences of said laws. Against pillagers, Communists, drug warriors, or even the State worshippers in academia, Natural Law provides no protection, alas. It fails against the last because you cannot prove that such Law is a moral ought – without resorting to some other moral axiom.

These two small works demolish common libertarian claims to have crossed the is-ought barrier. I literally felt vertigo when I read these in my grad school days. They are useful works for escaping Rothbard’s reality tunnel.

That said, I still use Natural Rights arguments – but more humbly. They provide a useful basis for resolving conflicts between fairness and liberty. But I cannot prove that Natural Rights should be preserved. That decision is inherently subjective.

Law and Economics

David Friedman dispenses with axiomatic morality and sticks with consequential arguments. In Law’s Order he provides a hard look at the economics of law.

And I do mean hard. This is not an easy work. I put it down years ago and have yet to resume. But I should. There is much good stuff here. Must reading for all lawyers and lawmakers.

Difficult != Profound

Statists have field days picking apart libertarian philosophy because they can. The works of the libertarian canon tend to be readable.

Universities prefer to assign difficult to read works; they make for better exercises in reading comprehension, even when the Great Works are completely and utterly stupid. Here are a couple of examples from my university days.

I don’t believe that Immanuel Kant was some kind of metaphysical super villain. But after reading his Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals several times I’m like: “WTF?? There’s nothing here!”

Seriously, there is no real argument.

Kant starts with a very questionable premise: Only the will can be moral. Then he derives his Categorical Imperative from this premise. In a nutshell: If it feels good, it cannot be a moral act since no willpower is involved.

That’s it. The rest is mostly mental meandering. Indeed, Kant himself backs away from the implications of this logic – while providing zero reasoning.

Maybe Kant’s other works are truly profound. Maybe this work got cred from his other accomplishments. I know not.

Whereas Kant’s work was less than meets the eye, these lectures by Georg Hegel are just plain batshit crazy.

His argument boils down to this: For history to follow a logical sequence, History has to be a conscious spirit. And if you don’t believe history to be logical, you are some kind of primitive caveman. Ergo…

The rest is all defensive selfus-interruptus. That this guy could ever be taken seriously makes me question the core of academia.

More Moral Philosophy

Self interest or self sacrifice? This is the question debated between the followers of Rand and Kant. C.S. Lewis transcends the question in The Screwtape Letters, where he makes the distinction between the negative self-sacrifice and the positive charity. Lewis was also a proponent of moral hedonism, a theme also found in his space trilogy.

The Economics of Government

Market failures are real, and libertarians are notorious for downplaying market failures. Fair enough. Let’s have some government to do the jobs the private sector won’t do and/or add some extra rules to make the private sector behave correctly.

But have a care! Government is not some dispassionate Olympian being. Governments are made up (and elected by) real people, with real mixes of selfish and noble motives.

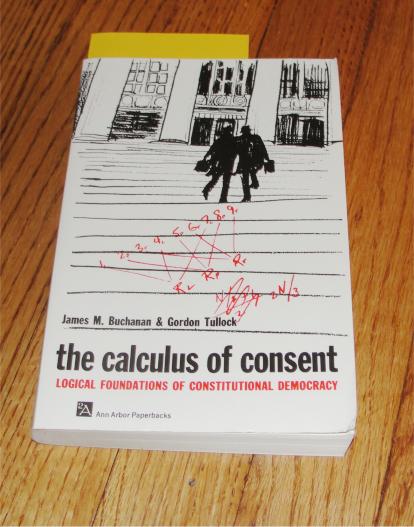

Apply the tools of economics to the actions of politicians and bureaucrats and you get the Public Choice school of economics. The Calculus of Consent is perhaps the most famous work on the subject. Co-author James Buchanan received a Nobel Prize for his work in the field. We are not talking about a fringe movement here.

Warning: The Calculus of Consent is a very difficult work. If you don’t have enough fluency in microeconomics, it is too difficult. This work is on my to-read list.

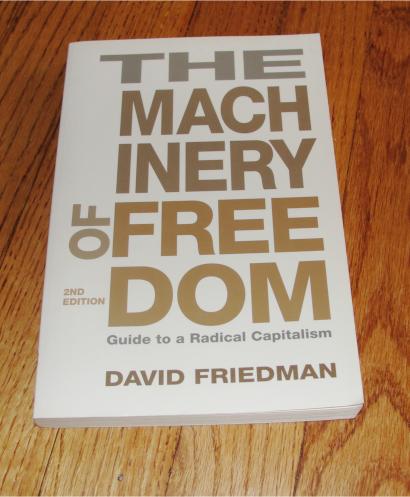

For a much more readable introduction to the economics of government, try The Machinery of Freedom by David D. Friedman. This is one of my favorite non-fiction books. I have given out quite a few copies over the years. Dr. Friedman makes an economic case for competitive government (anarcho-capitalism). I am no longer completely sold, but I still highly recommend this work. Those who would use government as a tool should be aware of the challenges.

Note: the picture is of the second edition. There is now a third edition available – it’s on my wish list…

Fun fact: the second edition – printed back in 1989 – includes the business model for ride sharing services such as Uber as a replacement for public transportation.

Lessons from the Physical World

Those who would attempt to derive the universe would do well to study the universe we have. There is much that philosophers, economists, and political scientists can learn from the physical world.

Central planning became all the rage at a time when scientists were making great strides studying tractable, linear, systems. I don’t think this was a coincidence. With the rise of the digital computer, scientists could take a closer look at equations that cannot be solved analytically – and the results are…weird and beautiful.

And humbling.

To be truly educated in the liberal arts sense of the world, one should have some exposure to chaos theory. Even surprisingly simple systems can be chaotic. Three variables suffice.

I got my exposure to the field by taking a course at the graduate level. So the book I read is not appropriate for most. But I hear that James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science is well written. Check it out.

Some of my socialist friends liked to pooh-pooh Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand metaphor as quaint, and obsolete. It’s not. It’s just an old fashioned description of negative feedback.

Then again, if free market economies were all negative feedback, economies would be stable. They aren’t. Positive feedback exists as well, resulting in instabilities.

Electronics provides many simple lessons in negative and positive feedback. The Art of Electronics by Horowitz and Hill provides a good start for the aspiring electronic tinkerer. I have the second edition. The third edition is on my own personal wish list.

Modern Advances in Philosophy

“Advance” and “philosophy” are words that don’t seem to belong in the same sentence. After all, they still read Plato at the universities. (They don’t read Newton in the physics departments usually. Advances in the physical sciences are taken for granted.)

But true advances do happen, but they aren’t necessarily labeled as philosophy. Some of the advances come from mathematics or even engineering.

For a good introduction to what modern mathematicians have been doing in the field of logic and consciousness, try Gödel, Escher, Bach, an Eternal Golden Braid by Douglass Hofstadter. This book oscillates between charming and difficult. I was given a copy in high school and have yet to finish it. But I have enjoyed the slow journey.

Logic acts on words, not reality directly. Alas, words do not map cleanly to reality. Plato noted the problem in his famous cave metaphor in The Republic. But Western Philosophy – and law – has marched on adding more and more words.

In the East, philosophers went in the other direction, and bemoaned the futility of words. Wise men ran schools on how to transcend words in order to experience reality directly.

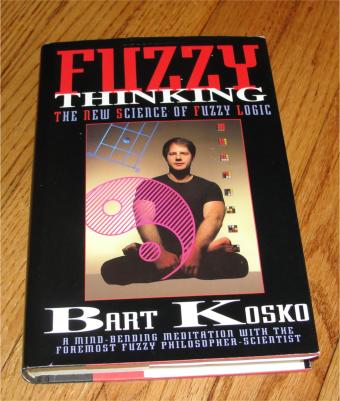

Fuzzy logic bridges the gap. It openly acknowledges that things only approximately fit our words and categories, but it also suggests that we can assign numbers to model how close the fit is. The resulting continuous logic can be used to design smarter machines. There is actual application.

The idea could be used for designing legal codes as well. We could shrink the law books by an order of magnitude by using fuzzy logic. Bart Kosko’s Fuzzy Thinking is a good introduction to the field.