A Case for Christian Communism

Acts 4:

32 The group of those who believed were of one heart and mind, and no one said that any of his possessions was his own, but everything was held in common.

33 With great power the apostles were giving testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was on them all.

34 For there was no one needy among them, because those who were owners of land or houses were selling them and bringing the proceeds from the sales

35 and placing them at the apostles' feet. The proceeds were distributed to each, as anyone had need.

(NET Bible®)

The first Christians were communists. This disturbs me greatly. Communism is a recipe for poverty. The Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock were communists; they starved. The Jamestown Virginia colonists tried communism; they starved. In the 20th century the Russians, Chinese, Cambodians, and Ethiopians gave communism a try. They starved. Communism imposed by government is an evil comparable to racism. Who did more evil: Hitler or Stalin? Run the numbers; then flip a coin. I have spent much of my adult life promoting the opposite of communism. But as a Christian, being opposed to the Apostles puts me in an awkward position at best.

And so I have long wrestled with the conflict between the Apostles’ decision and my own knowledge of economics and history. After meditating intensely on the matter, I think I have a viable resolution, which is this: the Apostles were inspired to set up a communal economy not because communism works well, but because it works so poorly.

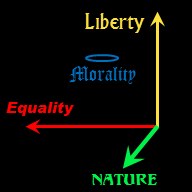

A market-based economic system allows strangers to benefit each other without caring or liking each other. Rational self-interest is often mutual interest [1]. Even enemies can be thus motived to trade for mutual benefit. If you are trying to encourage generally good outer behavior, a market economy is a beautiful thing.

But if you are trying to train people to be truly good from within, there is much to be said for communism. A commune requires true altruism, in greater quantity than most people can manage. It forces people out of thinking merely about themselves and their immediate loved ones to concerning themselves with everyone else in the community – for good or ill. When the community is working, all become concerned with the needs and abilities of other members of the community. This can be beautiful, and lead to intense feelings of belonging. But throw in a few freeloaders, and rot can set in quickly. Every claim of need or inability can be viewed with suspicion. Ayn Rand portrayed the phenomenon brilliantly in the Twentieth Century Motor Company subplot within Atlas Shrugged [2]. (Ayn Rand could be brilliant when in attack mode. Her positive statements of moral philosophy, on the other hand, were deeply flawed.)

The good of any requires the good of the many. A few sinners or slackers can poison the entire community. As soon as one person gets away with it, others are likely to follow. Spying and social pressure can become intense. For the creative individual who lacks charisma, such a society is oppressive indeed. (This is why uncharismatic nerds are attracted to libertarianism more than most.)

But there is an upside to being in such a pressure cooker environment: social pressure is an extremely powerful tool to break old habits and instill new habits. Modern experiment has showed it to be far more powerful than reason or willpower.

Communal living can be like a gym for working out the moral “muscles.”

We must complete the analogy, however. For physical muscles, too much time in the gym can lead to overtraining, to illness and weaker muscles. Similarly, the Soviet Union produced more envy, criminals and monsters than it produced saints. And forcing those not into muscle-building to spend time in the gym is a good way to manufacture future couch potatoes.

So while I can now appreciate the potential of voluntary communism, I still don’t think it is for everyone, and for most who try it, the arrangement should be temporary.

2 Thessalonians 3:

10 For even when we were with you, we used to give you this command: "If anyone is not willing to work, neither should he eat."

11 For we hear that some among you are living an undisciplined life, not doing their own work but meddling in the work of others.

12 Now such people we command and urge in the Lord Jesus Christ to work quietly and so provide their own food to eat.

13 But you, brothers and sisters, do not grow weary in doing what is right.

14 But if anyone does not obey our message through this letter, take note of him and do not associate closely with him, so that he may be ashamed.

15 Yet do not regard him as an enemy, but admonish him as a brother.

(NET Bible®)

Communal Living: Training for Leadership

To get what you want in a market system requires either making it for yourself, or trading your services to someone who wants what you are good at making. Those with specialized skills or knowledge can thrive with little in the way of charisma or leadership capabilities.

In a democratic commune, the only way you could can get your way is to convince the group. In a hierarchical commune, you must persuade the leadership. A commune needs extraordinary amounts of altruism to survive. Individual members of a commune need leadership and management skills to thrive.

By setting up the first churches as communes, the Apostles created a high intensity school for future church leaders. The early church was limited to leaders-in-training and obedient followers. Others tended to self-purge well before the church grew into a larger organization, outside the supervision of the original Apostles. After a stint in a commune, being an active leader or volunteer in a more modern style church is practically coasting. Indeed, there is enough mmph left over for leading the community at large as well.

Even in the small-government system envisioned by paleo conservatives and moderate libertarians, there would be churches, non-profit organizations, local governments, and businesses larger than family-sized. All organizations of size greater than one have communal aspects. Time spent in a commune is training for political and/or corporate leadership.

There are communists who go on to become successful capitalists – probably more than there are Objectivists in America’s corner offices.

Even the experience of partial communal living can be instructive. College fraternities have been known to generate future leaders.

So, even in the modern, more individualistic age, a Christian denomination could profit greatly by encouraging temporary stints of commune membership. These could be retreats for people who need to recharge their spiritual batteries or possibly part of the coming-of-age initiation. Communes should be limited to the zealous; unwilling slackers can ruin the dynamic, leading to the envy and resentment found in mandatory communist countries.

Having monks and nuns devote their entire lives to communal living, on the other hand, may be suboptimal. Great power comes from taking the experience of communal living out into the outside world.

1Rational self-interest is not always mutual interest, however. Market failures and externalities exist, a fact pure libertarians are loath to recognize.

2Part II Chapter X. "The Sign of the Dollar" Worth reading by itself even if you don't want to read the rest of the book. Double plus worth reading if you plan to start a commune.