A Warm and Fuzzy Foundation for Freedom

Why does the libertarian movement have a culture of overstatement? Why does the movement need organizations like the Advocates for Self Government to teach communications skills? The answers lie in the arguments given by some of the movement’s leading late thinkers, especially Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard. Both thinkers built their cases for liberty deductively, using a minimum of axioms. The problem comes when you look too closely at the roots of their arguments. Their axioms are not 100.00000% correct, and when you try to derive a philosophy from too few axioms, even tiny initial errors can compound into profoundly incorrect conclusions. And as I have already shown elsewhere, Ayn Rand’s starting axioms are more than a little bit incorrect. (I’ll get to Rothbard in the future.)

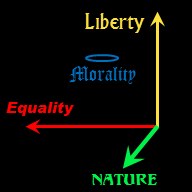

I’m intellectually lazy. I don’t try to derive the universe, or moral philosophy, from a few exact axioms. Extrapolation in general is difficult and dangerous. It is easier and safer to interpolate from observed truths whenever possible. By doing so I can make a strong case for a libertarian society, or something close to it, using three pillars, three understated fuzzy axioms. They are easily repeatable observations with generous error bars, vs. a single statement of Truth from some philosophical high place. Let us begin:

Freedom: it’s rather nice.

Freedom is good in and of itself. I don’t claim it is the only good. I do not claim we should abandon security, morality, charity or the environment for the cause of freedom. I simply say we shouldn’t toss away freedom frivolously. And yes, as a freedom lover I am willing to sacrifice some other values for reasons of liberty. Even if you could prove to me that socialism would result in more security and prosperity than capitalism, I would reject it.

This fuzzy axiom is a weak form of the Zero Aggression Principle beloved by many libertarians, since theft, fraud, slavery, taxation, and force initiation in general all violate freedom. But the Zero Aggression Principle (ZAP) quickly leads to extreme and unpleasant conclusions. ZAP implies that you cannot have government funded welfare even if the result would be poor and disabled people starving in the street. ZAP implies that all taxation other than user fees that you can opt out of is immoral. If the nation cannot defend itself with voluntary contributions, then it deserves to be conquered.

Freedom is an easy sell, especially in the United States where freedom is an essential part of our core mythos. The government schools still teach it. Freedom at all costs, however, appeals to few. To broaden our reach we need a second fuzzy axiom:

Freedom: it usually works.

Many people advocate big government not because they reject freedom, but because they know no other alternative to further some other important value. We who love liberty know better. Trade works to fulfill a great many human needs and desires. Charity can make up for many market failures. A great many government programs are unnecessary, inefficient, and/or counterproductive.

This is the utilitarian/consequentialist argument for liberty and it is powerful. But it is insufficient by itself, unless you overstate the case, making absurd statements like “Government doesn’t work.” Market failures are real. Government works, and sometimes works better than the market. Attempt to maximize utility without other considerations, and government grows to a dangerous degree. And that leads us to our third fuzzy axiom:

Government: it is dangerous.

Government is supposed to be dangerous – to criminals and foreign enemies. As such, government presents other dangers. Government is like nuclear energy, to update an old simile. All too often people mistake the government for “us” or “the will of the people.” Libertarians know better. Government leaders and government employees can have their own agendas. It is in the self-interest of both to make government grow beyond its optimal size. It’s simply a matter of drumming up business. Since government is a monopoly with the power to force people to buy, “drumming up business” works against the welfare of society unless the people diligently rein government in.

Public Choice economics describes and documents many “government failures,” areas where the interests of the governors and even voters diverge from the general welfare: public employee unions lobby for above market pay and below market accountability, legislators bring pork to their districts, corporate lobbyists loot the treasury, trade associations lobby for unnatural oligopolies.

These are easily documented, but they do not disprove the desirability of government. Anarchy is dangerous as well, likely more so than properly constituted republic. Moreover, we cannot justify a libertarian society on this pillar alone without resort to ridiculous conspiracy theories. The U.S. government is not ruled by malevolent monsters seeking to take away all our freedoms. Many of our leaders and civil servants are doing their best for the general welfare, often at personal cost.

The dangerous nature of government is a good tie-breaker for many decisions, however. Should the city pick up the garbage or provide tax-funded Internet service? Both services are natural near-monopolies. Garbage collection in a city is “necessary” and Internet service is becoming a modern necessity, so you are going to pay for these services regardless; little freedom is lost with the government solution. With economies of scale and no need to market, a city government can sometimes provide such services cheaper and better than private businesses.

The case against government ownership of these services is danger. The more services a city provides, the more government employees there are with interests at odds with the public welfare, and the harder it is for voters and elected officials to keep an eye on expenses. Moreover, in the case of Internet service, a future city administration might opt to monitor who looks at naughty web sites or perform other acts of surveillance. For these reasons it is often better to rely on private businesses to provide such services, even when the private business is more expensive and the government solution entails little immediate loss of freedom.

Understate. Over Demonstrate.

Build the case for liberty using only one of the three pillars above and you have to overstate your case if you want government really small. Do so, however, and the conversation immediately moves away from the case for liberty. Claim that the government should never tax or initiate force, and you challenge your audience to provide counter examples. A discussion of anarchy preempts your fine case against a truly bad government program. Claim that markets always work better than government and your audience quickly focuses on examples where government does indeed work quite well, instead of your good examples of actual government failure. Claim that government is run by a sinister cabal and your audience sees your tinfoil hat instead of the many easily documented examples of lower level nefarious activities.

Understate the case for smaller government, and you invite further discussion, more evidence. This is not a magic bullet which turns your audience into libertarians overnight, or even ever. It is, however, a critical tool to maintain credibility and keep minds open long enough to learn some benefits of liberty. And that, my friends, may well be enough, as we’ll see later.